As we reached the threshold of the Abbassian Traditional House, a childlike sense of excitement took root within my companion's heart. Like an impatient child eager for a mint chocolate, she moved through the ancient structure with unrestrained enthusiasm. My wife, always my confidante and partner in exploration, seemed to feel an insatiable thirst to devour every memory held within those walls. With indescribable eagerness, they whispered, "I'm going upstairs!" and in the blink of an eye, she had ascended the narrow, winding terracotta steps. I couldn't help but smile as I watched her become immersed in the rich tapestry of the mansion's history. With each step, the whispers of the building's untold stories echoed in her ears. She seemed to hear something amidst the stone and mortar that I either couldn't perceive or hadn't yet earned the right to understand. Yet, I could see the entirety of her experience reflected in the radiant smile that graced her face.

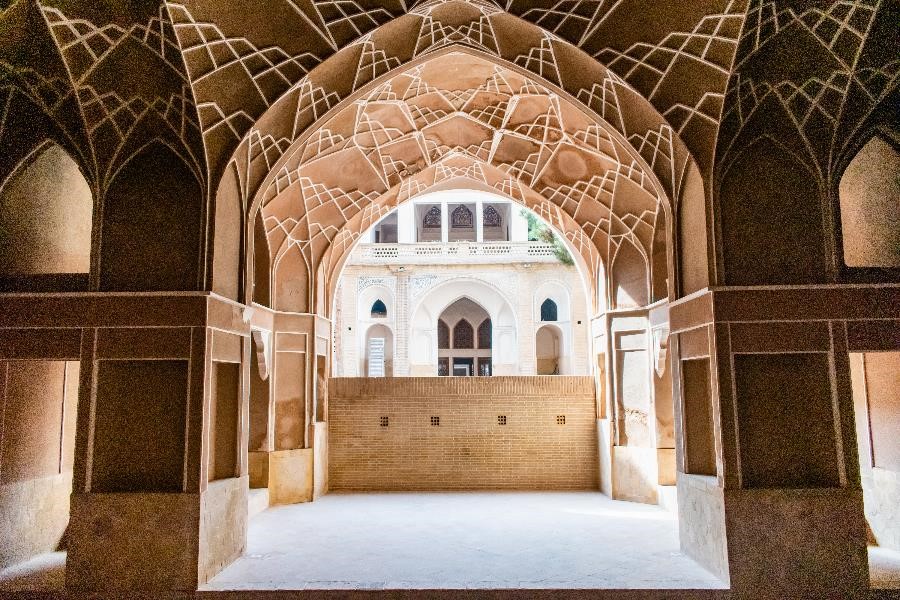

Stepping into the Abbassian House was an unparalleled experience amidst the traditional Iranian dwellings nestled in the heart of the desert. We had journeyed through time, into the depths of ancient Iranian history, and found ourselves immersed in the warm embrace of memories within this authentic house, enveloped in the pure joy of discovery and perception.

A heavy silence cast its shadow upon the façade of the hushed mansion. The house was devoid of any visitors. I should have sensed this as soon as we crossed the threshold. From the moment we entered, a melody resonated through the air, suggesting that no visitor had any desire to cross this ancient threshold. At the very least, it was safe to assume that we would be free from the company of others. As we approached the ticket counter, we were met with a tableau of absolute silence. A middle-aged man, who seemed to embody this silence itself, leaned against the wooden counter, lost in the depths of a profound slumber. The murmurs of passing time whispered in his ear, and he was a traveler in his own dreams, far removed from the world around him.

Emerging from the depths of the ticket booth's silence, the radio's voice drifted through the air. Music from a local radio, with its authentic melody, rode the waves of silence that filled the mansion. The radio host would occasionally murmur a poem between the melodies, but his voice only served to disrupt the music's harmony and rob it of its charm and tranquility. The sleeping man's eyes were knotted in a dream of silence, and nothing could disturb his peaceful slumber. Long minutes passed before we finally gathered our courage and, with trembling voices, pierced the thin veil of his reverie.

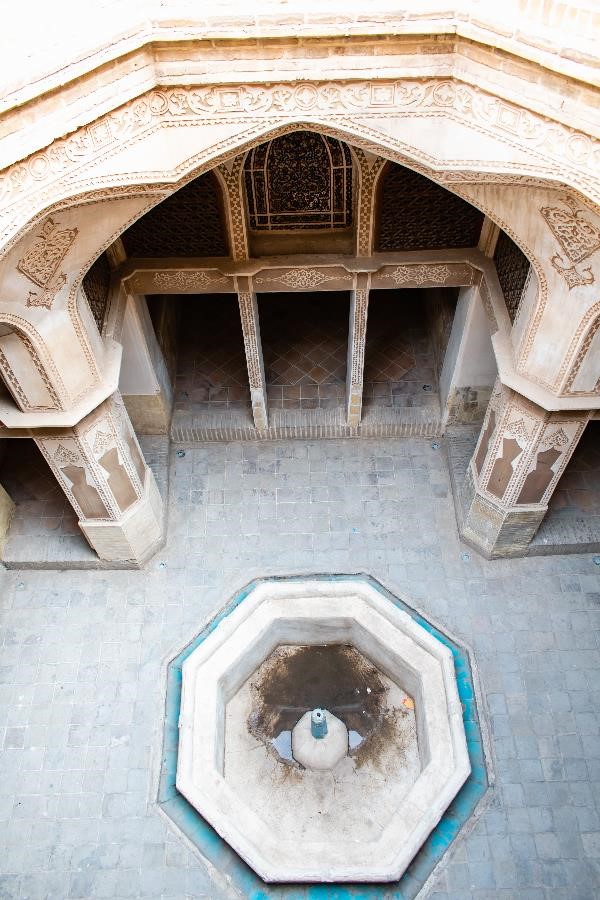

My wife's footsteps breathed a melody of unknown joy into the ancient veins of this desert house. Her voice echoed through the labyrinthine corridors and rooms, scattering her excitement and enthusiasm into the atmosphere. Apart from the sound of her footsteps echoing excitedly through the rooms and hallways of the house, there was also the sound of the small fountain in the central courtyard pond. The melody of the small fountain in the courtyard pond harmonized with the caress of a cool breeze. An orchestra of nature, with exquisite delicacy, caressed the symphony of silence in this old house. Amidst this, the gentle melody of traditional Iranian music imparted a mystical spirit to the space and whispered the untold secrets of the house. The murmurs of the people who had breathed life into the adobe walls of this house centuries ago.

Two turquoise jars, cracked by time, stood silently in the courtyard's corners, bearing witness to the years gone by. They held within them the unspoken secrets of the house's past residents. Amidst the autumnal landscape, two orange trees in the garden gifted the courtyard with the fragrance of spring through their blooming blossoms. Colorful flowerpots adorned the courtyard's corners, painting the sorrowful adobe walls with the vibrant hues of life.

Occasionally, the sound of my camera shutter would shatter the courtyard's tranquil silence, as if etching a trace of my presence into this ancient history. I disrupted the courtyard's harmonious symphony, attempting to convey my existence to these walls and their concealed history, "I am here too!"

Aside from the verdant hues of the garden plants, every color in the courtyard was a shade of the desert soil. The passage of time had etched its wear and tear on every corner. Unconsciously, the rhythm of my photographs had harmonized with the melody of the music, as if I too had a part in this symphony of silence and earthen paintings.

My wife's voice was no longer audible. It seemed she had ventured into the other courtyards in search of the secrets held by this storied house. As far as I knew, this old house had at least five separate courtyards, each one harboring a world of mysteries.

With each deep breath, the scent of damp earth enveloped me, infusing the spirit of this desert home into my very being. I am a captive of the world of scents. As if each fragrance holds an untold story, and each perfume conceals an unsolved mystery. I perceive the world around me through a myriad of scents, and with each breath, I am immersed in the boundless ocean of existence. My eyes delight in the beauty they behold, the softness of touching objects sends a delightful shiver through my body, melodies caress my soul, and flavors tantalize my taste buds. But the sweet scent of life is something else entirely; a profound and delicate sensation that cannot be seen with the eyes, touched with the hands, or heard with the ears. The scent of life is a fragrance that rises from the depths of my being and guides me to the very core of existence.

As I gazed upon the turquoise pool, tiny drops of fountain water splashed onto the dusty earthen tiles of the courtyard floor. These small drops, mingled with the scent of desert soil, created a potion of authenticity and antiquity, and as long as the fountain ran, this pure fragrance wafted through the air, keeping the spirit of this old house alive.

My entire photography kit consists of a simple, inexpensive camera. I believe it's the cheapest one on the market. I have two lenses: a wide-angle and a telephoto. I constantly have to switch between the two, which can be time-consuming and sometimes causes me to miss out on unique opportunities and fleeting moments. However, it also satisfies my desire for a simple and minimalist lifestyle. I usually start photographing with the telephoto lens. My preference is to capture the whole from its individual components. A movement from the parts to the whole.

With the telephoto lens, I was framing the details of one of the plasterwork designs in the house when suddenly, a familiar sound broke the harmonious silence. It was the sound of knocking, a rhythmic and unfamiliar pattern. While it didn't harmonize with the softness of the space, it carried a sense of mystery in its order. Repeated blows, a brief pause, and then a repeat. A muffled, deep sound, something in the world of fabrics and threads. Not like the sound of construction work, nor the echo of a hammer on a brick. The sound was deep, and the blows were muffled. When a hammer hits a brick, the sound echoes and reverberates through the air. But the sound was deep, and it quickly subsided after each blow.

Upon hearing this sound, every Iranian feels a sense of familiarity stirring within them. It's a familiar melody, the melody of carpet weaving workshops, but why here, in the heart of the Abbassian House-Museum? This contradiction unveiled an untold secret. The secret of an anonymous artist who, in this historic house, intertwined the threads of art into the soul of carpets. My telephoto lens was searching for a trace of this secret, for the hands of the artist who played the melody of the carpet in this solitude. Perhaps for younger generations this sound has less meaning, but the older one gets, the more this murmur comes alive. Once upon a time in this land, a carpet weaving workshop could be found in every city, in every alley and street. Once upon a time, the name of the carpet was synonymous with the name of Iran, and the sound of a carpet weaving workshop was a familiar melody for every Iranian.

The sound came from the courtyard where I was standing. It couldn't be from the other courtyards of the house. The sound was close. There are four doorways on the four sides of the courtyard. One of the entrances leads to another courtyard, and the other three lead to a part of the building. The cellar, the royal hall, the summer room, the winter room, and other rooms that are seen in the special and sustainable architecture of desert houses. The sound continues to reach the ears from the depths of the house. Repeated blows, a brief pause, and then a repeat.

The winter room, with its abundance of colored glass windows, was located to my left. Sunlight shone directly on it throughout the day, bathing the room in light. In times of cold, people's thoughts turned to creating a warm, sun-drenched haven. Thus, on the sunny side of the house, they would build a room that seemed to nestle in the sun's embrace. This room, as the beating heart of the house in the cold season, was a refuge for the household from the harsh winter cold, and its warmth caressed their souls and bodies. The sun, with its rays, bestowed its radiant warmth upon the inhabitants, keeping them safe from the biting cold and frost of winter in their secure haven. The door to the room was open, and I took a look inside. Nothing could be seen. The room was empty, and a layer of dust covered the earthenware tiles on the floor.

The entrance to the other courtyard was behind me, and to my right was the summer room. Unlike the winter room, this room did not receive even a single ray of sunlight during the day. It was a few steps below the level of the courtyard and offered a delightful coolness to its inhabitants in the summer heat. On the south side of the courtyard, hidden from the summer sun, cool and shady halls and porches were built to provide a refuge from the oppressive heat. These open spaces, called "summer rooms," were built around the main axis of the courtyard and often consisted of a hall or semi-open space. In desert cities like Yazd and Kashan, where the winters were also not harsh, summer rooms played a central role in daily life and were considered the most important living space in the house. These halls and porches, like other parts of the mansion, were adorned with beautiful decorations, although due to the openness of the space and the possibility of dust and dirt entering, these decorations were often simple and unadorned.

Old photographs of the house and the stages of its renovation were pasted on the walls of this room, but there was no other activity in it, and like the winter room, it was empty, and there too, a layer of dust covered the earthenware tiles on the floor.

The only option left was the room in front of me. It led downward with several steps. I think it was the basement of the house.

A basement, also known as a "payab" or "pa’ab," is the entrance to a qanat in the courtyards of houses and mosques. This space, often covered by a vault-shaped or domed porch, had a pool in its center where the cool water of the qanat flowed. In the scorching summer heat, basements served as natural refrigerators and were used to store food. The pleasant coolness of these spaces also made them an ideal place for rest and afternoon naps.

Some believe that there is a relationship between the basement and the "padiaw," a space that, according to Professor Pirnia, was transformed into a patio with the migration to Europe. Both spaces are adjacent to the building and along the path of water flow, and they benefit from its coolness. However, there are also differences between the two spaces. The patio is usually a more open and larger space than the basement and has a wider range of uses, including as a place for rest, recreation, and gatherings. In contrast, the basement was more commonly used as a source of water and a natural refrigerator.

The mysterious sound, with its same rhythmic pattern, continued to reach my ears, beckoning me towards it. Without a doubt, I set off towards the sound. An unknown and irresistible force was pulling me into the depths of this untold secret.

As I reached the foot of the stairs, a vague shadow emerged in that dimly lit room. It was as if a web of secrets was woven into that space. Something resembling a loom also stood in the middle of the room. The door to the basement was open, and something was inviting me inside. I told myself that there was probably no harm in entering the room.

The door to the basement was made of old wood, and small colored glass panes emitted a soft and pleasant light into it. The two leaves of the door were open. I entered the cellar. Now I could better see what was going on there. As soon as I entered, I saw a 75-year-old man weaving in a corner of the basement. But not a carpet, he was weaving a zilu. It was strange. The city of Meybod is registered as a world city of zilu, so I did not expect to see a zilu loom in Kashan.

The art of "zilu" has an ancient history, rooted in the history of pre-Islamic Iran and is one of the most important handicrafts and arts of this ancient land. In ancient texts, zilu is rarely mentioned, and only in a few cases is it mentioned as a carpet in mosques. However, the available evidence shows that zilu weaving has a long history and was among the known carpets in the early centuries of Islam and was popular in Iran. The extensive use of zilu in religious places has created a deep connection between this art and religious architecture and has linked its name to mosques and holy places. So much so that even today, zilu can be found among the common rugs in mosques with a long history.

The old man seemed lost in the world of threads and weft, oblivious to my presence in that delightful solitude. The sound of my regular knocking, which could be heard from the courtyard, was clearer here. Repeated blows, a short silence, and a repetition of this mysterious rhythm. With caution, I took a step towards the old man. I wanted to share in this ancient secret with him.

The old man had a bald head and wore a knitted vest over his striped shirt. He wore simple cloth pants, and his hands looked rough and calloused from having woven with them so much. The knitted vest stood out on his thin frame, and as if in contrast to the stripes of his shirt, it whispered the story of the contrast between tradition and modernity. The simple cloth pants were made of desert soil and, in their many folds and wrinkles, displayed the untold secrets of years gone by. His hands were the roadmap of his life. Their roughness and harshness told the tale of years of work and effort in the darkness of basements, workshops, and cellars. The unkempt stubble on the old man's face was the brush of time, which had painted patterns of hardship and suffering on the canvas of his face, which was nothing strange for an old man who lived in one of the traditional cities of Iran. A face that the scorching desert sun had not had the chance to shine on, and its pallor told the tale of years of living underground. The old man's furrowed brows and scowling gaze added an aura of silence and weight to the basement space. Untold secrets lay hidden in the depths of his eyes, and his presence placed a burden of silence and weight on the shoulders of any stranger.

In this desert land, the people were like the desert itself: quiet and reserved. Silence was their old companion, and in it, they whispered their unspoken words. But at the same time, open-heartedness and kindness shone a warm light from their eyes, inviting strangers into their loving embrace.

But this old man seemed not to be of this desert or of this people. His scowling face and heavy silence were a stark contrast to the peaceful spirit of the desert. The old man did not fit in at all with my mental image of the desert people.

With a perfunctory greeting, I addressed the old man engrossed in his work and asked, "May I take a few pictures?"

My trembling voice echoed in the heavy silence of the workshop. A fear of his sharp, piercing gaze had taken root in my heart. I still didn't quite know what had drawn my attention to that old, dark solitude. Perhaps it was the cracked and worn jug, a relic of bygone days, or perhaps the delicacy of the old man's fingers as he patiently and meticulously wove designs onto the weft of the zilu. I had no idea exactly what I wanted to take pictures of. The old man's creation seemed to cast a shadow over my entire being, and my concern was more with obtaining his permission than with photography. I thought that this simple permission was the only way to escape his heavy, scowling gaze.

I paused for a moment, waiting for a response from the old man, but a complete silence reigned over the space. Time seemed to have no interest in moving in that corner of the world. The old man, oblivious to me, continued his work. It was clear that my presence didn't matter to him in the slightest.

Suddenly, he turned his head slowly and his sharp gaze locked with mine. It was as if he wanted to see into the depths of my soul. A shiver ran down my spine. In that look, there was a combination of authority and indifference that is rarely found in anyone's eyes. A heavy silence hung in the air for a few more seconds, and we both took this short time to assess each other. I was there for the audacity of entering his solitude, and he was there to evaluate my intentions. Finally, without saying a word, the old man shook his head slowly and, with the utmost reluctance, granted permission to take pictures.

I took a deep breath and thanked him from the bottom of my heart. I felt like I had been released from the spell of the old man's powerful eyes. I bet even Stalin didn't have such a menacing frown. And immediately he went back to weaving. I took my camera and started taking pictures. Each click of the shutter captured a memory of that moment in my camera's reminiscence.

But engrossed in my work, I had forgotten the old man. I was mesmerized by the finesse and precision of his movements. His hands danced a delicate and beautiful dance with the weft and warp of the zilu. I paused for a moment and stared at him again. For a few minutes, I was captivated by that heavy gaze and that absolute silence. In those moments, the world outside that basement had become devoid of any movement or impulse for me.

What was going on in the old man's mind at that moment? God knows what insults he was hurling at me in his heart! "What does this camera-wielding fool want from me? With his ridiculous tone and his strange clothes!" And probably something like that must have been going through the old man's head. If he liked me or at least enjoyed seeing me, a hint of a smile would have crossed his lips. But alas, not a twitch on his lips. Not a word, not an expression, and no indication that he didn't mind my presence in the basement? Well, if people weren't supposed to come around here, they should have closed the wooden door to the basement or at least put a sign on the door that said "No entry!"

I still had the telephoto lens on my camera, and I was so excited about the old man's presence that I forgot to change the camera settings. With the same settings, I was taking pictures of the semi-dark basement from the bright, sunny courtyard. When I checked the photos, I was met with a sea of blackness. The weight of the old man's presence had also cast a shadow over the darkness of the photos.

I hurriedly changed the camera settings. I did this in a hurry, not to reach an ideal point, but to get the camera ready for another shot as soon as possible. I was afraid to stand there idle. The zilu weaving machine, its delicate weft and warp, the colorful threads scattered in a corner, the woven edge of the zilu, the old man's hands that skillfully breathed life into the weft and warp of the zilu, and the tools and equipment that were scattered around the cellar, one after the other, became the subjects of my camera.

With each picture I took, it was as if a burden of the weight of that silence and that heavy gaze was lifted from my shoulders. The camera shutter was like a tranquilizer, soothing the anxiety inside me. I was doing camera-therapy on myself. The dread of the old man's presence was still rooted in me, but I was slowly getting used to the environment. As time went on, I was more comfortable taking pictures of him. Of his artistic hands that delicately tied knot after knot, creating art, and of his thoughtful, scowling face.

I knew I should change the lens. Common sense dictated that I should use the 35mm lens, or the wide-angle lens. But that unknown fear held me back from doing so. Fear that if I changed the lens, my train of thought would be broken and I would once again be trapped in that heavy silence and that scowling gaze. And so, all the photos became breathtaking close-ups. Frames detached from the environment. A way to cut the subject out of the environment. And that too, that haunting, quiet, dimly lit, and not very friendly environment.

Standing behind the old man, I was on the lookout for that perfect moment. The weft and warp of the zilu and the dance of the bright colors of the threads showed off in my camera's frame. But my goal was not just to capture this superficial beauty, but to capture the soul of this work of art, the soul of the old artist's hands in my photographs. Now that I didn't have the courage to change the lens, all my effort was to make the close-ups as meaningful as possible.

The camera's focus was on the warp of the rug, but it was as if an invisible force was pulling me towards the old man. In the third frame, the old man suddenly turned and faced the camera. A deep and piercing look was in his eyes. My body trembled. The coldness of the old man's gaze penetrated to the depths of my being. Fear, unconsciously, gripped my entire being. After all, what danger could a seventy-something-year-old man pose? But logic had given way to emotion in that moment. I was a prisoner of the situation. I didn't know what to say or what to do. Was I supposed to do something or say something at all?

I slowly lowered the camera. My mind was racing for a sentence to appease him. Thousands of words were tangled in my mind. I usually speak well and use words well when interacting with others, but the old man's inherent silence cast a shadow over my mind.

"Did I offend you in some way?"

"Did I do something wrong?"

I never thought I would apologize to someone for something I didn't do. But then, something strange happened. The sun came out from behind the clouds and illuminated the old man's darkness. In the blink of an eye, everything changed.

The old man's stern, bitter, and frowning face transformed in a split second. A warm and kind smile spread across his lips. His eyes pierced through my soul and reached into my spirit. This time, not to scratch my feelings or imprison my soul, but to caress my being! The general posture of the old man's body had also changed. A paternal calmness had embraced him. He looked like a kind grandfather who had jumped out of a story from the Arabian Nights. If I had taken a portrait of the old man's previous face and now took another picture of him, it would be hard to believe that this was the same frowning and sullen man from a few seconds ago. The enigma in the old man's gaze had vanished. A simple, life-filled look poured from his eyes. A lively smile was on his face. He looked at least ten years younger!

He was staring at me. He was like a magnifying glass zoomed in on an unknown point in my being. Not exactly at my face, but staring at a spot near my shoulder. Involuntarily, I followed his gaze. There was nothing on my shoulder. Everything on my shoulder was the same as when I had entered this basement a few minutes ago. I continued his gaze, passing over my shoulder and going behind me. And suddenly, as if the veil of that deep gaze had been lifted!

A woman in her early thirties, with large black eyes and long black hair, part of which was hidden under a beautiful cream-colored shawl, stood behind me. Her presence had put a happy tune on the old man's soul and a smile on his lips!

My wife was standing on the steps a meter behind me, and with her presence, the grumpy old man's face bloomed. At that moment, I didn't know whether my wife's surprise and pale face or the old man's ear-to-ear grin attracted more attention! It even seemed that the light in the basement had increased. Stranger than the old man's smiling and open face were his lips. Those lips finally opened. With his sweet Kashani accent, he began to speak:

"Come in. Welcome. This is a zilu weaving workshop. The loom is not mine, of course, and I work for someone else. I have been around a large carpet loom since I was a child. I weave both zilu and carpet, as well as shawl, and anything else you can think of. Come down here, daughter, why are you standing there? Come on, let me tell you what zilu is and how it's made? ..."

And the old man talked and laughed for the next thirty minutes!